Vintage Thursday

Horace Greeley Johnson: 'Edison of underwear'

by Patrik Vander Velden

The man called the "Edison of underwear" came to his inspiration in the dead of the night, "almost like a dream." Horace Greeley Johnson, pictured left, was a 42-year-old knitting room supervisor at Cooper Underwear Co., the precursor to Jockey International, Inc. His idea for the Kenosha Klosed-Krotch union suit that September in 1909 would earn him wealth and turn a small mill into the world's largest maker of knit long johns.

Johnson shook his sleeping wife Olevia. "Wake up I want you to sew something for me," he said. At his direction she stitched multicolored cloth remnants from her scrap bag. And the inventor became his first model for a practical innovation in men's underwear that would make a visit to the bathroom more civilized. It was the perfect complement to indoor plumbing and central heating. Until then the 19th century male wore underwear strictly for warmth. The style was a two-piece outfit, button-up shirt and bulky baggy drawers. In those days before central heating, great-grandpa kept his drawers on without change from one Saturday night bath to the next. In winter, it was too darned cold in the bedroom to strip down to the buff any more often than necessary.

Red flannel with fleece lining was the vogue. It was believed woolen underwear would ward off rheumatism. Wool was the only fiber that would take the red cochineal dye of the era and hold without running. Americans soon learned any flannel that was red had to be made of pure wool. Horace Johnson was born in 1867 in Hesper, Ontario, Canada. At 16, he was working in his father's knitting mill learning the trade and tinkering with the mechanical knitting machines. In the underwear business, technology was constantly being improved, permitting the manufacturing of better fitting and less bulky garments. Johnson came up with some of those improvements while working for his father, and later, at other mills in Canada and the United States.

In September 1901, he accepted a job in Kenosha with the just-opened Cooper Underwear Co. Not long after he arrived, he met Olevia, who worked as a knitter in the mill. Soon they were married. The local firm had been founded by three brothers, Charles, Willis and Henry Cooper. A pioneer in the direct marketing of stockings to retailers, the Cooper company was small but growing. It suffered a stunning setback in 1903, however, when the tragic Iroquois Theater fire in Chicago took the lives of Charles and Willis, leaving Henry to run the business alone.

As the new century began, underwear consisted of a shirt and drawers combination. But it was uncomfortable. The double layer of cloth around the wearer's midsection was bulky and the bottoms drooped. A one-piece union suit seemed the solution, but that, too, presented problems. As one Cooper salesman put it, "Some provision had to be developed so that the seat could be opened when the occasion demanded it." The trapdoor was tried, but the drop seat was hard to unbutton and even harder to rebutton. Besides that, during laundering the hand-cranked wringers kept breaking the buttons. Next came the so-called open crotch type union suit, featuring strategically located button-less flaps. But it was criticized as a "humpy, lumpy, creasy, baggy proposition, chafing and cutting your nethers."

When Johnson's brainstorm struck, the solution, like most breakthroughs, was ingeniously simple. His design featured two knit pieces that formed an overlapped X which could be drawn apart when required. He called it the Klosed Krotch union suit. Its opening was diagonal from a point above the crotch on the left side to a point below it, down on the right leg. It resulted in a single thickness of cloth through the sensitive area. And it revolutionized the underwear market.

Johnson and Henry Cooper, owner of the factory, jointly patented the design. Patent No. 973,200 was issued on Oct. 18, 1910, and Klosed Krotch underwear was first marketed under the Cooper White Cat label. The inventor soon was being called "Klosed Krotch" Johnson, a nickname the family tolerated as a joke, recalls his granddaughter, Barbara Hunt, 1836 89th Place. "After all," Hunt says, "our money was in underwear." Her grandfather, she remembers, was a man with social graces, who would dip his hat to the ladies, even though he was busily working and his hands were dirty. He enjoyed a good cigar, keeping them in a mahogany box which stood next to a brass floorstand ashtray near the living room fireplace.

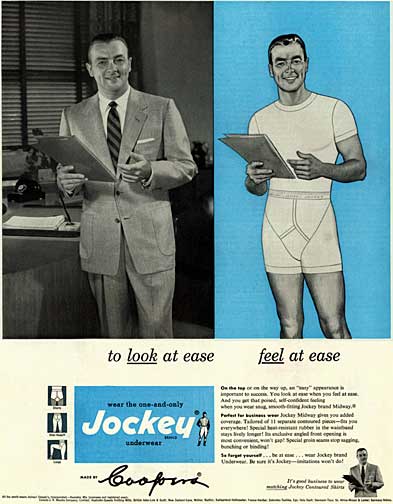

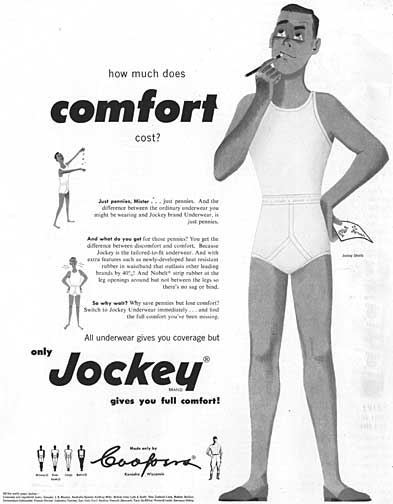

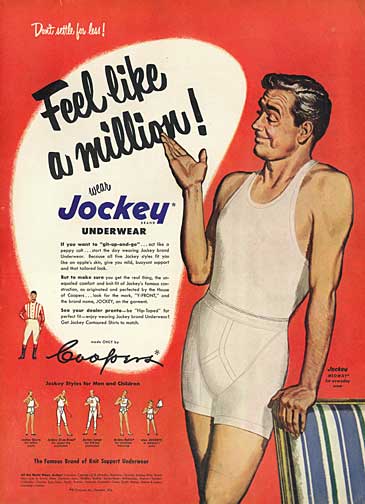

Johnson wore spats and a Panama hat...and, of course, his own invention. Johnson was a member of the Elks and enjoyed a few lines of bowling and playing pinochle with friends and family. He became a naturalized US citizen in 1910. In 1911 Cooper initiated a nationwide magazine advertising campaign, the likes of which were unknown in the underwear business. Illustrated by one of the best known artists of the time, Joseph C. Leyendecker, the ads appeared first in the Saturday Evening Post. One even displayed boldly a selection of women's underwear.

Under license from Cooper, other underwear makers soon adopted Johnson's design. Royalty profits allowed Johnson to retire from active duties at the mill. Hunt says her mother, Hazel Testard, later recounted that whenever other school children talked about their fathers' jobs, she had to admit that her retired father had none. "The other youngsters all felt sorry for her," Hunt says. Some Cooper competitors simply stole the design, refusing to pay royalties for its use. The Kenosha company sued and Johnson frequently traveled the country with a company lawyer, arguing the protracted lawsuits. A 1913 trade paper advertisement urged "customers not to take chances buying infringing goods until the courts decide." In the end, the Supreme Court ruled against Cooper, but the long legal fight had been good publicity for the firm's products. The high court ruling was precedent setting, effectively ending a manufacturer's right to patent a clothing design. Still, for years, most competitors agreed to continue paying licensing fees to use Johnson's design. His widow continued to receive small royalty checks into the 1950s.

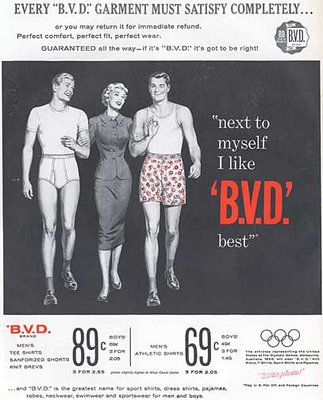

But innovations continued in the underwear industry. In 1915, a competitor, Bradley, Voorhees and Day brought out a light cotton union suit made of a fabric called nainsook. It was cut and sewed, not knit. The garment was sleeveless and had quarter-length legs. It soon became popular as the B.V.D. The very lawsuit Coopers had lost now brought benefits. Cooper could safely copy the B.V.D. design, which it did, incorporating into its new lightweight union suit the familiar Klosed Krotch.

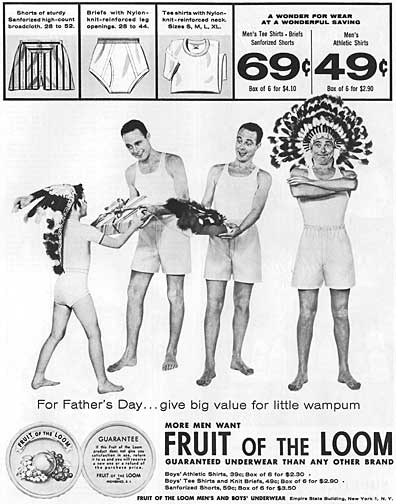

Underwear has fashion changes, too. A major change occurred after World War I, when young veterans began wearing the sort of knit skivvy shirts and separate cotton shorts they had worn in the Navy. By 1930, the traditional union suit was considered an old man's style. There were even more startling style changes ahead for Cooper's underwear business. Johnson's son-in-law, Bill Testard, took up the innovator's mantle, establishing the company's first research and development department. In the post-World War II Jockey era, Testard created the bikini brief and promoted colored underwear, well before it became vogue.

The Depression years wiped out much of the wealth Johnson had earned from his Klosed Krotch design, his granddaughter says. But not before he had seen to his family's educational needs. He paid for the education of two nephews, one of whom became a doctor, the other an attorney. He had a firm view of the sexes, though, believing that Man was the provider, Woman, the keeper of the home, destined for the domestic sphere, not higher education. He also bought a 140-acre farm on Lake Winnebago, near Neenah, for his wife's parents. When he visited, he enjoyed horseback riding. The Johnson home at 6028 Eighth Ave., today, is part of the Woman's Club. A handsome mansion, it was large enough for the children to roller-skate in a third floor ballroom. However, they were forbidden to slide down the banister. It contained a parlor and sitting room on the south side, a library and playroom on the north, with a huge dining room, butler's pantry, kitchen and cold room in the rear. The second story had seven bedrooms, including two for maids. There was, however, a single bathroom, but it was supplemented by large marble wash bowls in several bedrooms.

In his retirement, Johnson enjoyed traveling by car across the country. Winters were spent in Florida or Arizona. Yet he considered Wisconsin the most beautiful place of all with its varied landscape of lake shores, forests, fields, farms and cities, Hunt says. Horace Johnson died Nov. 27, 1936, at the age of 69. He was buried in Sunset Ridge Cemetery.<<

4 comments:

I'm always learning something cool from you :)

But I must ask-- what the FUCK are those things on the glass coffee table, 2nd to last picture??

Umm I have no idea Larry They look like some sort of glass globes.

Vintage Thursday is lovely. As always!

Thanks Brad

Post a Comment